![]()

![]() Sir Walter Scott

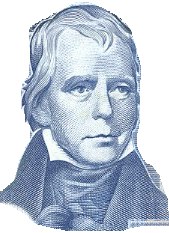

Sir Walter Scott

![]() (1771-1832).

(1771-1832).

Scott, the "great romancer," was trained as a lawyer. Steeped in the traditions and customs of the Scottish highlands, Scott's novels are backdropped with the events of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and set with scenes laid out in remote and uncultivated districts. His novels are filled with superstitious and mannerly characters, entangled with the intrigues of war, religion, and politics. Though Scott wrote verse he is at his best when writing prose. Scott "told his story in incident, and not in reflection or in adjective."

Scott discovered that, indeed, facts are better than fiction; he wrote of events from real life and not "the fine-spun cobwebs of the brain."1 Scott's writings were politically based, he equated the mobs of the previous centuries to the "modern rabble" of his day, those who were rising up against tradition and custom such as the mobs of the French Revolution. He backed his friends who had a "horror of all reform, civil, political or religious." During his time he was a most popular figure with numerous readers and admirers, "quarrelling which of his novels is the best, opposing character to character, quoting passage against passage." William Hazlitt thought Scott to be a genius, but one "who took the wrong side and defended it by unfair means."

(These notes mostly made from Hazlitt's The Spirit of the Age; also see Hazlitt's The Plain Speaker for additional comments on Scott. For another essay on Scott, see

Bagehot's Literary Studies. Scott's works are readily available on the 'NET ![]() .)

.)

_______________________________

-

Note:

1 "All is fresh, as from the hand of nature: by going

a century or two back and laying the scene in a

remote and uncultivated district, all becomes new

and startling in the present advanced period. Highland

manners, characters, scenery, superstitions:

Northern dialect and costume: the wars, the religion,

and politics of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries,

give a charming and wholesome relief to the

fastidious refinement and 'over-laboured lassitude' of

modern readers, like the effect of plunging a nervous

valetudinarian into a cold bath. ...

"Sir Walter has found out (O rare discovery) that

facts are better than fiction, that there is no romance

like the romance of real life, and that, if we can but

arrive at what men feel, do, and say in striking and

singular situations, the result will be 'more lively,

audible, and full of vent,' than the fine-spun cobwebs

of the brain. With reverence be it spoken, he is like

the man who, having to imitate the squeaking of a

pig upon the stage, brought the animal under his

coat with him. Our author has conjured up the actual

people he has to deal with, or as much as he could

get of them, in 'their habits as they lived.' He has

ransacked old chronicles, and poured the contents

upon his page; he has squeezed out musty records;

he has consulted I wayfaring pilgrims, bed-rid sybils.

He has invoked the spirits of the air; he has conversed

with the living and the dead, and let them tell

their story their own way; and by borrowing of others

has enriched his own genius with everlasting variety,

truth, and freedom. He has taken his materials from

the original, authentic sources in large concrete

masses, and not tampered with or too much frittered,

them away." (William Hazlitt's Sir Walter Scott.)

Here is what Sir Hugh Walpole had to write about Scott:

"It is the fashion now, I know, to sneer at Scot, to declare him unread and unreadable, to laugh at his anachronisms, to be appalled by his cumbrous sentences, to shudder before his simpering heroes, to be aghast at his material view. These things run in cycles; we are just now [c.1925] all for sophistication, for technique and arrangement and for a proper dignity in letters, but some day some one will come along who will clear away a little of the clambering ivy and the twisting weeds that have grown thick about the stones of that splendid old building. An enormous amount of critical self-satisfied cliche has to be thrown away, and then with a new view there will be astonishment, I fancy, for a good many people." (Reading: An Essay (New York: Harper, 1927, p. 23)

_______________________________

Found this material Helpful?

_______________________________

![]() [UP]

[UP]

[BIOGRAPHIES JUMP PAGE]

[HOME]

2011 (2019)