Book #1: Acadia.

Book #1: Acadia.Our scene shifts back to the bastions and bulwarks of Louisbourg and the amateur army which had landed in whale boats on the shores of Gabarus Bay. There then followed, as we have seen, "a short but smart engagement." The few brave Frenchmen who had met their attackers on the beach, other than those that were captured, fled to the safety of their stone walls. The colonial troops then "filled the country." The French inhabitants who lived and worked within a mile or two of the walls of Louisbourg ran to the gates and did not apparently spend time gathering up their possessions.1 The New Englanders were disorganized and undisciplined. Directly they found an empty French structure, they put it to the torch. The officers, when they finally caught up with their enthusiastic raiders were to take them to task; not so much that they were to make certain French families homeless by their activities, but because many of these structures housed very valuable supplies which the invaders might well have come to use, for example, sails and cables.2

The older and more experienced of the New Englanders (no less enthusiastic but possessed of an understanding that first things came first) continued to stick to the shores, or returned after taking a peek at this fabled fortress: supplies had to be landed and a camp set up.3 This was to take time and some planning as there was considerable difficulty in landing guns and stores "for want of a harbour" and "the surf running very high" and the men "obliged to wade into the water to their middles and often higher."4 By the 3rd, all the men meant to be ashore, were ashore. And, while there was yet some heavy work to do in getting the cannon off the ships and placed before the walls of Louisbourg, the view at this early point, is -- "We all seemed to of one heart and things are in a good posture."5

I now tell of an event that occurred just after the New Englanders landed and pushed to the outskirts of their objective; a very fortunate event, indeed; an event which was yet another piece of good luck for these amateurs who had "a tough nut to crack"; an event which made a critical difference in the capture of this prize: Fortress Louisbourg. The colonial invaders were to take the Royal Battery away from the French without a shot being fired. But before telling of that event we best remind ourselves of the physical positioning of the principal defences of Louisbourg.

| The Mouth of Louisbourg Harbour. Click on the Island Battery, the Royal Battery and the Lighthouse point. |

In describing the fortifications of Louisbourg in the earlier part of this work, it was pointed out that the defence of the town depended on two fortified gun batteries located beyond the reaches of the main fort, itself stuck on a rocky peninsula which acts as a lower jaw at the mouth of the harbour. (See clickable map.) This mouth stretches for about a mile to the upper jaw, Lighthouse Point. It is through this mouth that a ship must sail in order to get to the harbour side of the town. The outer edge of the peninsula, the eastern facing edge of Louisbourg, is impregnable having as it does a piece of Nova Scotian "iron bound coast," an eastern facing shore lined with a granite face and smashed continually with the breaking waters of the North Atlantic. These shore conditions extend out to the end of the peninsula on which Louisbourg is located, and beyond, in a submerged fashion, half way out into the harbour's mouth to an island located about midway between the inclosing jaws of the peninsula and Lighthouse Point. No ship can enter to the south of this island, between the island and the peninsula; she would be grounded and soon come to pieces from the action of the churning waters against the graveled granite just below the surface. The channel into the harbour was to the north of this small island, between it and Lighthouse Point. On this island the French built a small independent fort with cannon; the Island Battery, with thirty-six guns broadside to the narrow entrance.6 A second independent fort was located on the shore of the harbour immediately opposite, northwest, situated like a uvula to the mouth of the harbour. Thus, it was, that any ship trying to get into Louisbourg harbour would face a deadly cross-fire between the Island Battery and the shore battery.7

The shore battery to which we just referred, it needs be pointed out, was not only located opposite the entrance of the harbour but also opposite, or nearly so, to the north-western edge of the town. (Again, see clickable map.) Old Louisbourg, as has been stated, is located on a peninsula, the neck of which wore its heavily fortified walls; the town is within and is principally served by is docks located on the north side of the peninsula and behind the walls; but the north side of Louisbourg is comparatively exposed, as it must be, if it is to carry out its water borne trading activities at the edge of the harbour waters. The shore battery was located about two miles along the curved shore of the harbour, but only about a mile across the harbour, in a straight line, just as a cannon ball would fly. This shore battery was very much the pride of the French engineers: it was called the Royal Battery. It was a very impressive stone structure complete with walls; towers; and twenty-eight 42 pounders, mounted and pointed to the mouth of the harbour.8 The French were just then (1744/45) in the process of carrying out improvements to the Battery's land-side walls; in preparation, they had leveled certain areas leaving openings which were vulnerable to attack. There was to this fortification, more generally a serious geographical flaw: inland of it, there was higher ground which an invading enemy might easily command.9

Given the above description, one might now imagine the surprise of our colonial raiders, when the very next day after they land, a detachment sneaks up to take a look over the brow of the hill in behind the Grand Battery and find that it was deserted; the French had left it for them, guns and all. Well, these colonial English couldn't believe their luck. The small force which occupied the Royal Battery was headed up by Colonel William Vaughan; it was to be Vaughn's moment of glory.

One version10 has it that Vaughan did it with twelve men. They had just finished, without any resistance, it would appear, torching "several large storehouses," likely somewhere between the fort and the Grand Battery. These storehouses were filled with combustible naval supplies (pitch, tar, cordage, and wood); it sent up a glorious signal. Being handy, the small group decided to have a peek at the Grand Battery: -- And what to their surprise! No one was home! We quote from a journal kept by one of the New Englanders:

"This morning we had an alarm in the camp supposing there was a sally from the town against us we ran to meet them but found ourselves mistaken. I had a great mind to see the Grand Battery, so with five other of our company I went towards it and as I was a going, about thirty more fell in with us. We came in the back of a hill within long Musket shot and fired at the said fort and finding no Resistance I was Minded to go and did with about a dozen men setting a guard to the northward, should we be assaulted [when we saw] two Frenchmen whom we immediately took prisoners [along] with two women and a child. [We] then went in after some others to the said Grand fort and found it deserted."11Fairfax Downey describes the event this way:

"The Battery was strangely silent. There was a lifeless look to it; no smoke from the chimneys, a soldier pointed out. But even the impetuous Vaughan was not going to be drawn into a trap with a rush to storm a fort of that size with thirteen men. He beckoned an expendable one of them, a Cape Cod Indian, gave him two lusty swigs from his silver flash of brandy and told him to take a look inside. The Indian slithered through the brush like a snake and up and over a low-leveled stretch of rampart. He vanished, reappeared, stood up and waved them forward. Muskets cocked - it might still be a trap - the colonials crawled through embrasures, squeezed past the big spiked 42s, and entered the deserted stronghold. Aside from themselves, the only living things in the fort were a forlorn woman, left behind in the haste of departure, and a puppy. Vaughan called over eighteen-year-old William Tufts of Massachusetts, borrowed his bright red coat, and had it hoisted up the bare flagstaff."12

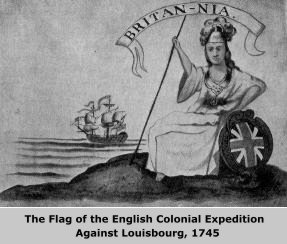

A message was sent to Pepperrell, -- sweet to all the colonials only just then trying to take up positions before the looming fortifications of Louisbourg; and sweetest of all to Vaughan -- "May it please your Honour to be informed that by the grace of God and the courage of 13 men, I entered the Royal Battery about 9 o'clock, and am waiting for reinforcement and a flag."13 Incidentally the New Englanders had made up their own flag and brought it with them, a crude drawing of Lady Britannia sitting with banner and a union jack shield.

Why did the French desert one of their prime defence positions. This decision, as more generally the defeat of the French, at Louisbourg, in 1745 -- can be laid at the feet of Governor Du Chambon. The fact is: that as soon as the New Englanders arrived, Duchambon hauled everything in, turtlelike, and hunkered with his people behind the stone walls of Louisbourg. The governor did consult with his advisers, but the only discussion, somewhat heated, that was had was whether the battery should be totally destroyed, or not. Verrier, the proud builder of the Royal Battery must have been very upset to see, so early in the conflict, the French give up the "Royal Battery"; but, he was totally distracted by the suggestion that it should be blown up; a suggestion to which he was "firmly opposed." Verrier won out; the governor did not insist; and, Louisbourg suffered. "The battery would be abandoned but not destroyed, its gun would be spiked and its stores of foodstuffs and munitions evacuated to Louisbourg." The work was too hurriedly carried out; and, while steel rods were driven into the touch holes, the anxious soldiers neglected to smash "either trunnions or carriages" and left "virtually all the stores behind in their flight into Louisbourg."14

In short order, as we have seen, Vaughan and his small band entered this fortification of which the French were so proud and which the French believed they could reoccupy directly the New Englanders got tired and went back where they came from. Their pride was pricked when they spied from their ramparts, across the harbour, and instantly took note of the red "flag" flying from their Royal Battery. Soon they had "four boatloads of troops" being rowed across the bay; determined they were, to go back, retake, and make sure that their earlier spiking job was good enough. But as few as the New Englanders were, they now, in respect to Royal Battery, had the upper hand; they occupied an impressive fortified position which could hardly be taken from the shore. The approaching barges were peppered with musket balls. More then musket balls were flying: the French boys at the main batteries located at both Louisbourg proper and at the island decided to join in and were lobbing cannon balls at the Royal Battery, which, as most fell short, thereby only served in the colonial defence. The French troops in the boats, thus, were getting shot at from the front and the back; with the arrival of fresh New England troops, the meager French attempt to regain the Royal Battery came to an end and a hasty retreat was called. The Royal Battery (also known as the Grand Battery) from this point on was to remain firmly in English hands.

By May 3rd, the armourers of the enterprising New Englanders, headed up by Major Seth Pomeroy, had drilled out the spiked vents of three of the big guns at the Grand Battery; and had them leveled; and, in time had them doing the deadly work for which they were designed.15 The inhabitants of Louisbourg were soon to feel the effect as deadly projectiles dropped directly into the town. As one resident of Louisbourg bewailed, "the enemy saluted us with our own cannon, and made a terrific fire, smashing everything within range."16

In time, most all of the big guns of the Royal battery were unspiked and made operational. Samuel Waldo, who was put in charge of the Grand Battery's guns was certainly impressed with them, "as good pieces as we could desire." The problem was, "they devoured too much powder." Waldo feared he couldn't keep them going. Not, however, for lack of balls! The reader will recall that the optimistic New Englanders had brought large cannon balls along which would just fit these big French 42 pounders.17 However, due to falling levels of gun powder,18 the New Englanders could not keep up the intensity of the cannonading to any great extent; at any rate the most serious problem was that, "we are in great want of good gunners that have a disposition to be sober in the daytime."19 Here Waldo puts his finger on the most difficult problem which faced the commanders of the New England forces, to which we will refer.

And so we see, that within three to four days of their arrival, the invading New Englanders were in full charge of the fields outside of the walls of Louisbourg. They had with considerable ease, with thanks to a thoughtless move on the part of the French, captured 36 big guns which they could have never brought, landed and emplaced; and which, in turn, were used with terrifying effect on the French people harbouring within their walls. The English had much, so far, for which to be thankful and none in that age were embarrassed to get down on their knees under the direction of their religious ministers and offer to their maker their thanks.20 So far, so good: but there was siege work ahead; and, too, death and disappointment.

[NEXT: Pt. 4, Ch. 9 - Siege Work.]