Book #1: Acadia.

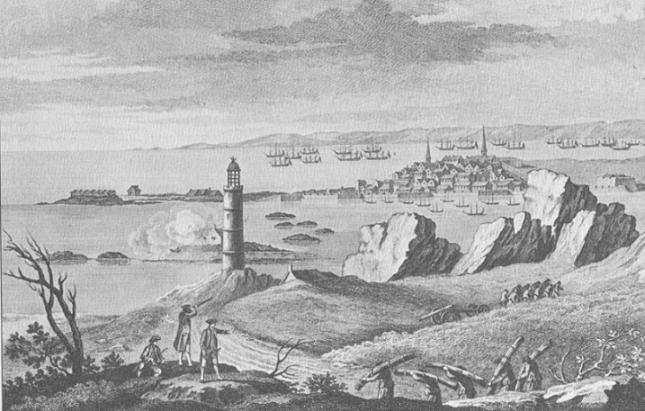

Book #1: Acadia.The fortifications of Louisbourg were in bad condition. The damage which had come about from the 1745 siege had not been fully repaired.1 The French had taken the precaution of demolishing the Royal Battery2 (see map) with its 36 guns, not again would these guns be used by besiegers to bombard the exposed town as was the case in 1745, though the English in 1758 were able to occupy the defensive works of the Royal Battery and mount guns of their own to shell the town.3

In addition to the civilian population at Louisbourg there were 5637 military men, divided up between those army men that were at the garrison (3031) and the marines (2606) that had come in with the French naval ships earlier that spring. By the time the British were ashore, certainly by the next day, on June 7th, most all of these men defending Louisbourg were behind the walls of their Fortress.4 Indeed, that evening, at about seven o'clock the second contingent of the Cambis regiment (the first had arrived the day before and had been stationed along the shore) arrived at the back of Louisbourg harbour having just completed their march overland from Baie des Espagnols (Spanish Bay, present day Sydney). The French sent launches over the harbour so to convoy them safely to the fortified harbour front of Louisbourg.5

Their failure to repulse the English at the beaches left everyone from Governor Drucour, on down, in poor spirits. Their duty was now clear: it was to keep the invaders out until reinforcements arrived or until winter came to freeze the British in their position; or, more generally, to tie up the British so that they could not go on to the French citadel at Quebec. Drucour had a warning that an invasion was coming; his allies, the Indians, had reported that there was a large gathering at Halifax, and, indeed, had reported the progress of the fleet as it made its way up the coast. He had called in the Port Toulose and Port Dauphin garrisons (see nos. 14 & 17 on map); and, "two dépôts of provisions were made on the Mire."6

The population at Louisbourg,7 due to the English blockade of the previous season, had just come through a most difficult time. During the winter, "not a family had an once of flour in the house." Not only had there been a shortage of food but there had been a lot of snow that winter, the last of which was still on the ground as of May 12th.8 It must be remembered, too, due to the actions of the English on the mainland that Louisbourg was the refuge of a number of Acadians and Indians.9

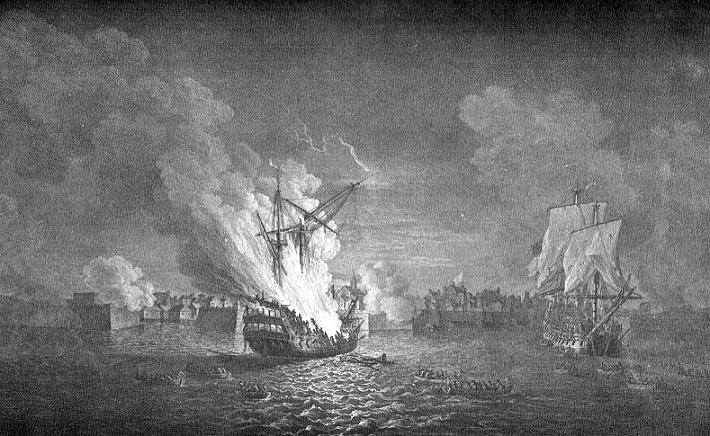

The French had intended that they should be at Louisbourg in as an impressive strength as they were the season before. There was a fleet from Toulon under M. de la Clue, but this fleet, while still in the Mediterranean sighted a much larger British fleet under Vice Admiral Osborn. The French fleet ran into the Spanish port of Cartagena, and there remained bottled up. Admiral Hawke had similar success with another French fleet just off the French coast by La Rochelle and Rochefort.10 However, six ships slipped away from Brest, and managed to reach Louisbourg during March.11 By April, as we have seen, Commodore, Sir Charles Hardy