Book #2: Settlement, Revolution & War.

Book #2: Settlement, Revolution & War.

"A populace never rebels from passion for attack, but from impatience of suffering."In 1775, the opening volleys of American Revolution exploded at Lexington. Though the great orators of the time -- and they were outstanding -- would certainly have grabbed a musket, those on Lexington Green, or behind the fences and trees on the road to Concord, or those stationed at the top of Bunker Hill, were but regular men who had come to the end of their tethers. They had become convinced that it was time to take a stand. We have seen where the English parliament in response to the troubles at Boston passed a series of acts, the Intolerable Acts, which led the civilian leaders of the colonies to meet at Philadelphia, on September 5th, 1774, The First Continental Congress. It passed measures affecting the relations of the colonies such as the forbidding of the importation of English wares and to support the people of Massachusetts Bay in their opposition against the Intolerable Acts. It then issued proclamations to the colonies, both north and south, which called for their support. At Virginia, the largest colony in America, one with the greatest ties and more English-like than any other, delegates were called together on March 23rd, 1775. The meeting took place in St. John's Church in Richmond. A number of the delegates were abhorred by the notion that they should take steps which might lead to war with the mother-country. The resolution was presented by Patrick Henry. Before the vote was taken, he delivered a speech in support. He stood, silent at first, then he spoke quietly and proceeded gradually to increase his speech in force and in loudness reaching at the end a crescendo that still echoes and will likely always echo in the hearts of men. I quote but a small part of this stirring speech:

(Burke, "On the Causes of the Present Discontents," 1770.)

"Gentlemen may cry, Peace, Peace! ... The next gale that sweeps from the North will bring to our ears the clash of resounding arms! ... Is life so dear, or peace so sweet, as to be purchased at the price of chains and slavery! ... I know not what course others may take; but as for me, give me liberty or give me death!"Thomas Jefferson, that great Virginian to which we had occasion to refer in considering the intellectual underpinnings of the American Revolution (see Chapter 7), summed up why it was necessary for American patriots to take up arms against the parent country.

"The colonies were taxed internally and externally; their essential interests sacrificed to individuals in Great Britain; their legislatures suspended; charters annulled; trials by jurors taken away; their persons subjected to transportation across the Atlantic, and to trial by foreign judicatories; their supplications for redress thought beneath answer, themselves published as cowards in the councils of their mother country, and courts of Europe; armed troops sent amongst them, to enforce submission to these violences; and actual hostilities commenced against them. No alternative was presented, but resistance or unconditional submission. Between these there could be no hesitation. They closed in the appeal to arms."1

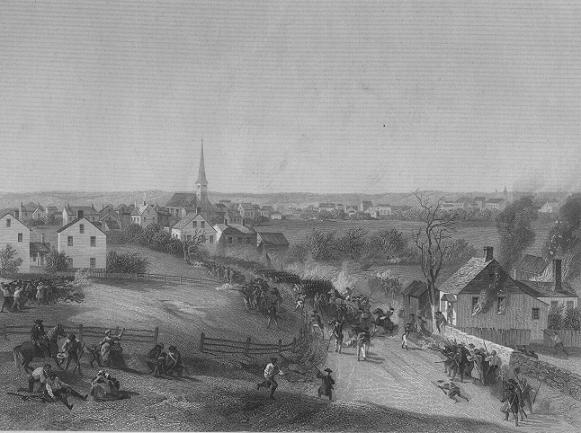

_________On April 18th, 1775, General Gage receiving word that there was military stores at Concord despatched 800 men to capture these stores. Secrecy was vital to the success of their plan, but the country was roused by colonial riders that had gone in advance of the British troops.2 Thus it was when the British marched into Lexington there was 70 militiamen drawn up to oppose them. After a brief engagement, during which several colonials were killed, the militia withdrew. The British continued their march to Concord, where they fought another battle which forced the British to make a harried retreat to Boston. When the British got back to the safety of their encampment at Boston, they figured out their losses: 73 dead and over 200 wounded or missing.3

|

Behind the fences and trees on the road to Concord. Chappel/Smillie |

The truth, we might observe, of what happened on the Lexington common has been much obscured by both the colonial and the British propagandists. "It is significant that the Whigs' version of the battle, replete with British atrocities in all their gruesome detail, was the first to reach the people of England and America." The delay of the British in getting their account out of what happened, was "fatal to the loyalist cause." As Burke pointed out the difficulties of adversaries separated by an ocean, "Seas roll, and months pass, between the order and the execution; and the want of a speedy explanation of a single point is enough to defeat an whole system."4

It was thus because of the great distance that the British commanders at Boston were to be quite on their own. The events at Lexington and Concord made it clear that the trouble in New England had now come down to guns and blood. The population had responded and men from all over were gathering. The men of Cambridge, a community just outside of Boston, and many more, held themselves out as being ready to respond to an emergency within a minute's notice; thus the Minutemen came into being.

While the British commanders thought about the matter and considered what step if any they should next take, the rebels took the initiative. The Americans had managed to get some heavy guns mounted on high ground on the shore opposite Boston, at Charlestown, thus to overlook Boston Harbor. It was thought from this high vantage point that shots might be lobed down on the British ships anchored in Boston Harbor. This situation having developed, the British had but two choices, either dislodge these cannon or abandon Boston.

On the morning of June 17th, 1775, the British ferried 1,500 British soldiers across Boston harbor on barges with a view to making a frontal attack on the bunkered position of the Americans on top of the hill at Charlestown. General Howe led a contingent around the base of the hill to cut off the expected retreat of the American forces as the first British contingent came at them from the front. Those holding Bunker Hill, it is to be acknowledged, were tired men of no particular military experience and while reinforcements were expected, they did not arrive. The British troops marched up the hill in formation. The Americans were overrun by the superior British forces, however, it was done with a loss of a thousand dead and wounded.5 The Americans, though they lost their position, apparently suffered only 150 killed and 300 wounded; and though 30 were captured most of the able bodied Americans managed to disappear into the countryside.6

Our devoted chronicler of Liverpool, Simeon Perkins made note of the events at Bunker Hill:

27th June, Tuesday: "Capt. White, Plymouth, arrives from Boston with an officer and sergeant on board. He brings news of an engagement between the King's troops and the provincialists at Bunker Hill. Charlestown is burt to ashes."

If the British authority back in London did not know it, the soldiers in America did. Having from April to June, come through Lexington, Concord and Bunker Hill -- the British commanders in America knew they were in for it. General John Burgoyne (1723-92): "After a fatal procrastination, not only of vigorous measures but of preparations for such, we took a step as decisive as the passage of the Rubicon, and now find ourselves plunged at once in a most serious war without a single requisition, gunpowder excepted, for carrying it on."7

The news that fighting had broken out in America, once it finally got back to England, was greeted with considerable dismay. Even the man in the street was at first to take the side of the king against his ungrateful cousins in America. On August 23rd, 1775, George III signed a proclamation in respect to Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition; it was to be read widely, there and abroad.8 The royal governors of the colonies thought to make up their own proclamations which were read out before the official one came over from England. We see where Perkins wrote in his diary on July 30th: "The Governor's proclamation [dated July 5th], forbidding all intercourse with New England rebels, was read."

The outbursts at Boston, were outbursts at Boston: the place had given the British authorities nothing but trouble since December in 1773 when some of the worst of the Boston rabble threw valuable chests of tea into Boston Harbour, and now in 1775 we see them shooting and killing His Majesty's soldiers. The royal governors throughout the colonies were very uneasy. They hoped that the trouble would not go beyond Boston, where it seemed there existed the greatest collection of hotheads. Nova Scotia had at this time more of a connection to Massachusetts then any of the other colonies. The history of these two English provinces was intertwined, indeed, Annapolis Royal, before the founding of Halifax in 1749, took its orders from Boston ever since, in 1710, English forces took the place (then known as Port Royal) away from the French.9 Having conquered French American territories, the English are seen beginning in 1760 to make the effort to settle English speaking people in Nova Scotia. By the end of the year, 1760, as one author was to put it, "Annapolis County had a new Massachusetts, Kings County a new Connecticut, and the present Hants County a new Rhode Island. The whole Valley was a new, New England, with a population of nearly 2000 people."10 Governor Legge of Nova Scotia had good reason to be uneasy about the events which occurred in 1775, at Lexington and Concord during April, and Bunker Hill during June. On July 31st, 1775, Governor Legge took his pen in hand and wrote to his masters in London:

"Our inhabitants of Passamaquoddy and Saint John's river are wholly from New England, as are the greatest part of the inhabitants of Annapolis river, and those of the townships of Cornwallis, Horton, Falmouth and Newport, some of which are not forty miles from this town [Halifax]; that by reason of their connection with the people of New England, little or no dependance can be placed on the militia there, to make any resistance against them; that many in this town are disaffected, on whom, likewise, I can have no great dependency; that should such an attempt be made, I dread the consequences. To convince your lordship how alarming our situation is, it was no sooner known that a quantity of hay was purchased for the horse in Boston, than a stack of 8 or 10 tons, which happened to be in an open field, was maliciously set on fire and destroyed; that since that, the buildings in the navy yard have been set on fire, but timely discovered and extinguished, -- and from the place it happened, where no fire is ever carried, and near the magazine of powder, it is certain, without all doubt, a malicious design to destroy that yard. The perpetrators have not yet been discovered. The exigencies at present have required almost all the king's troops from hence. There remain here only 36 effective men, as per the return enclosed. I have ordered these to do duty near the magazine for its protection, and at the ordnance store, not leaving myself a sentry. I have also ordered about 30 of the militia to do duty all night, and parole the streets."11

So it was, that Legge cast an anxious eye over the remoter parts of his domain, and thus to give his impressions in a letter to Lord Dartmouth. Legge was of the view that he could not rely on those who had recently come from Massachusetts, those of the Passamaquoddy, the Saint John and the Annapolis Rivers, and those of the townships of Cornwallis, Horton, Falmouth, Newport. Upon them Governor Legge declared, "little or no dependence can be placed" in respect to the defense of Nova Scotia. And so Governor Legge worried. At Boston General Gage was faced with a real shooting war. Most all of the British forces were concentrated at Boston with Gage.12 Governor Legge, since 1768, had but only a few dozen regular British soldiers with him at Halifax. Legge knew he was in no position to fight off an invasion or an insurrection. Legge was indeed fixed on the horns of a dilemma: should he collect up and arm the population so that he may then be in a position to fight off an invasion knowing that in so doing he would but assist an insurrection should it materialize.13 He determined to trust the population and signed orders, so to raise the militia, a civilian army. He determined to get the inhabitants together in their various communities and to form them up into regular bodies and train them in the Art of War.

So Governor Legge, having no choice, placed his faith and confidence in the people, to place reliance upon them. First, in order of events, was to formally bind those who were to report to him by an oath of loyal allegiance. These were the days, we should remind ourselves, where a solemn or formal appeal to God, such as is an oath, meant more than in the secular days in which we now live. Written agreements were prepared calling for signatures under oath to be signed "by all the councillors, judges, J.P.'s, grand jurors and others in October of 1775."14 That November, 1775, two bills were passed by the legislature, the one to call out the militia and the other to raise taxes for its support.15 The members, by and large, were to all stand up and give loyal addresses. Thus the legal machinery was in place. Each functionary swore their royal allegiance. The next step was to send the orders and commands out to the various communities requiring that able bodied men be formed up into their respective militia groups. The governor, in this respect, was to meet with considerable resistance which came in the form of petitions sent to him at Halifax.16

The people of Yarmouth, who were not so much worried about repelling invaders as much as they worried about being sent off to fight in New England, wrote: "All of us profess to be true friends and loyal subjects to George our King. We were almost all of us born in New England. We have fathers, brothers and sisters in that country. Divided betwixt natural affection to our nearest relatives and good faith and friendship to our King and country, we want to know if it may be permitted etc."17 This plea of the Yarmouth men for neutrality was refused. A compromise was worked out, however, whereby assurances were given that "the militia would not be removed from their habitations except in case of invasion."18

At Cumberland, the men pleaded their "indigent circumstances." And continued: "We do not fear danger from the Americans unless the militia bill is enforced. ... Should any person or persons presume to molest us in our present situation we are always ready to defend ourselves and our property." The Cumberland farmers but pointed to recent history. In being asked to fight their invading brothers from New England, was that not the same situation that the Acadians -- who worked the same farms but 25 years earlier -- had been put in by being asked to fight their invading brothers from Quebec; was it not the same predicament; did it not bring with it the same disadvantages. If the militiamen were mobilized their families would die of hunger. At Cumberland, the men plainly stated that they could not comply with the law. Approximately two hundred and fifty signed, fifty of them were Acadians, indeed two of the signatories were members of the House.

The same concerns and responses were to come in from most all of the rural areas of Nova Scotia, including, Annapolis, King's, Onslow and Truro.19 The general attitude of the men of these places was that they were prepared to form up but did not want to be drawn away from their farms and families."20 Certain communities -- notably Halifax, Lunenburg, and St. Mary's Bay (Acadians)21 -- were more enthusiastic in getting their men together to fight the rebels of New England. The impressions at Halifax, as 1775 wound down, was that Quebec had been overrun and that Gage was clinging by a toehold at Boston. As we will see, the impression as to Quebec was wrong, the one about Gage was correct.

Michael Francklin, a proven friend to both the Indian and Acadian, needed to use his considerable talent to convince the replanted New Englanders where their best interests lie. I quote, once again, Professor Kerr22:

"Writing from Windsor on March 3rd, this popular officer [Francklin] informed Governor Legge that the people were not reluctant to defend the colony, but did not want to see their families ruined.' Five days later, he reported further that 300 men in the townships of 'Windsor, Newport, Falmouth, Horton, Cornwallis and 200 in Cobequid23 and Cumberland -- the very townships which had so alarmed Stanton in November -- were ready to enroll themselves voluntarily, and enter into a formal association under oath for defence of the province."24

Those at Halifax, as the year 1775 came to an end, were of the belief that it was very likely that Nova Scotia was to be invaded just as sure as Quebec had been. A good number of the Nova Scotians had heard, that September, that hundreds of men were on the Kennebec River heading for Quebec.25 The Americans were quite confident that if they landed a sufficient force in Canada that a large uprising among the French would jell and in the result the British overthrown. They figured that the French population were unhappy with the British, it having been only but 15 years since the British had taken Quebec by force of arms. The Americans, it would appear, did not give sufficient weight to the historical fact, that for the French at Quebec, it was the New Englanders who were thought of as the enemy and had been since the early 1600s. What had not been calculated, too, was that the British administration at Quebec these past 15 years was mild and considerate26 and quite unlike the despotic rule of the French administration which the French had experienced before war's end. It is necessary to touch briefly on the American invasion of Quebec. The American colonel, Benedict Arnold made his way with his forces (1,100 men in canoes) to Quebec by way of the Kennebec and Chaudière rivers. At the same time, the American generals, Schuyler and Montgomery with their forces went by way of Lake Champlain. Arriving at Montreal in November, Schuyler (Schuyler became ill) and Montgomery found that the British had deserted Montreal. Arnold's route, we should mention, was badly advised, and, on route, they "suffered great losses and had exhausted their provisions."27 Arnold's forces were cut by one half due mainly to desertions. In any event, the combined American forces attacked the citadel of Quebec. The Americans were repelled and Montgomery was killed. They then spent a cold Canadian winter outside of the gates. In the spring the enterprise was abandoned and by the 18th of June they had entirely withdrawn from Canada.28 Now, my point is, that the efforts made by Arnold and Montgomery that winter to conquer Quebec was to cause considerable alarm at the beginning of the new year in 1776. Governor Legge at Nova Scotia wrote the Earl of Dartmouth: "the great advances the rebels are making in Canada, by conquering all the interior parts -- investing Quebec, which is supposed before this time to be in their hands, and their determined resolution of making a conquest of this province, are very alarming."29

As the year 1775 closed, Governor Legge at Nova Scotia was not as concerned as he had been earlier when first he heard of the shooting on Lexington Green and particularly when he heard of how better than a thousand British soldiers had met their end charging up Bunker Hill. It seemed, though, that things had settled down and that the fighting had been restricted to Boston and the environs. But then there was the spotty information coming out of Quebec, and the very large question whether the garrison at Quebec would be able to hold on (it did). Legge's call to raise a militia did not meet with much enthusiasm through out the province, though his call did net him about 400 men.30 England, too, had finally sent him some help. At the end of October a regular regiment, the 27th, arrived from England. British naval forces, too, were present at Nova Scotia. Admiral Graves was on station and he sent some of his frigates to the Bay of Fundy. So, unlike earlier in the year, Legge had something more than a skeleton force. In December he reported that he had at his disposal 980 men, 446 of whom were fit for duty.31 Overall Governor Legge was satisfied that his position was secure. He reported, that there were no disorders in Nova Scotia as were revealed in Massachusetts.32

[NEXT: Pt. 2, Ch. 11 - "The Events of 1776."]