Book #2: Settlement, Revolution & War.

Book #2: Settlement, Revolution & War.

The Napoleonic Wars (1793-1805)

In June of 1789, the French Revolution against the nobility and the clergy had formally begun. Four years, four terrible years for France, passed. On January 21st, 1793, Louis XVI was beheaded. Diplomatic relations were severed and the King of England sent the French ambassador packing. France invaded England's ally, Holland. On February 1st, France declared war on England. Within weeks, the news of these events arrived at Nova Scotia. By the spring of 1793 Nova Scotians knew that they were, once again, at war with the French. The historian, Beamish Murdoch wrote of the formal notice of war.

"Mr. Dundas, in his letter dated 'Whitehall, 9 Feb'y., 1793,' informed the lieutenant governor that 'The persons exercising the supreme authority in France' had declared war against the king of England on the first of that month - that 'letters of marque or commissions of privateers' would be 'granted in the usual manner,' and assurance was given to the owners of all armed ships and vessels, that his majesty would consider them as having a just claim to the king's share of all French ships and property which they might make prize of. Homeward bound merchantmen were also advised to wait for convoy."1

From my readings I have not been able to see where French warships came into Nova Scotian waters.2 Generally, French warships were obliged to stick close to home. The British were in charge of the high seas. They were at the height of their power3, even if the British sailors demonstrated their unhappiness.4 In May, 1798, Nelson re-entered the Mediterranean. In August, he destroyed the French fleet off of Egypt. Nelson's victory at the Battle of the Nile re-established Britain's hold on the Mediterranean and locked up Bonaparte and his army. By 1800, Napoleon had managed to slip back from Egypt. France made him First Consul (dictator) and the little general re-energized her. Italy was taken once again at Marengo. This event led the European princes to lay down their arms and make peace. England was left alone to deal with France.5

Great Britain was alone for periods of time in the fight against Napoleonic France. But never was she alone in North America; she had her North American colonies, chief among them was that of Nova Scotia. The United States in pursuit of trade was happy to load up vessels with American goods to be delivered to France. With the sanction of the British Crown, Nova Scotian privateers were only too happy to take vessels freighted with goods at New York or Boston and destined for French ports. Take them forcefully and run them back to Halifax to be declared by the Admiralty Court as carrying contraband of war. Judicial sales were conducted, the contraband sold, and both the privateer and the Crown would pocket the proceeds.6

To appreciate how busy Liverpool was during this period (1793-1805), we need but examine the careers of the Charles Mary Wentworth and the Rover.7 The first of these two was active in the years 1798 and on; the other seemed to have started up in 1800.

The first reference we see to the Charles Mary Wentworth was Perkins' entry of the 31st of July, 1798: "... Captain Joseph Freeman ... has got his Commission for the Privateer. The Governor8 has named her the Charles Mary Wentworth. The vessel carried 75 men & boys."9

A privateer shipped more men than she needed to sail the vessel or needed for fighting, if indeed a fight was what was necessary.10 A prize crew would be put aboard, viz, a few men headed by a trusted "Prize captain" would go out of the privateer and onto the prize. As a particular cruise was extended and as she captured prizes, the privateer slowly exhausted herself of men to the point where she was obliged to sail home to pick up her full crew, and to carry out repairs and to resupply.

The first prize to fall into the net of the Charles Mary Wentworth was the Morning Star. A prize crew sailed her into Liverpool Harbour on November 27th, 1798. She was a Brig. She had sugar and coffee in her holds. With her prize crew in charge, the Morning Star sailed under "American Colours." The thought being, I suppose, that she may well be ignored by other American ships, and, if stopped by a British patrol, prize papers could be produced. The Morning Star was captured on the 26th of October off the north side of Cuba. "She was from Jamaica, bound to Philadelphia, where she is owned. John Gorham is the prize master. They left the privateer on the first of the month all well on board." On December 16th, the Charles Mary Wentworth sailed into Liverpool Harbour to the greetings of "a gun & 3 cheers. All well on board." Other than the Morning Star, I can give no accounting of the prizes. An examination of the Admiralty Court records of Bermuda and of Halifax may well tell the story. In any event, not too many days passed before the owners of the Charles Mary Wentworth were to gather together to make a decision to return their privateer back to sea. "18 Dec: ... At evening the 8 owners of the ship Charles Mary Wentworth meet at Captain Parker's, and agree to fit the ship out on another cruise, as soon as may be." On February 2nd, 1799, she did just that. On May 11th, she was back at Liverpool with prizes, one being "a large topsail schooner." The prizes had cocoa in their holds. That fall, on October 16th, "The owners of the Privateers meet at my [Perkins'] office. Appoint Captain Joseph Freeman to the command of the Duke of Kent; Captain Thomas Parker to the Charles M. Wentworth; Captain John Barrs, Junr., to the Schooner [Lord Spencer] lately purchased." We see that on October 19th, "All three of the privateers are entering men. The Duke had about 30; the Charles near the same; the Lord Spencer about 20." The Court of Admiralty having condemned the captured vessels, on November 18th, "an auction of the Duke of Kent's prizes, and remainder of the Charles Mary Wentworth's prizes" was held. The vessels and their cargoes were to be sold off, separately. The vessels themselves were spruced up and buyers sailed in from other ports in Nova Scotia.11 The prize sales being over and with privateering profits realized, on November 27th, the three privateers - the Duke of Kent, the Charles Mary Wentworth & the Lord Spencer sailed out of Liverpool, together. The Duke12 mustered 95; the C. M. Wentworth, 79; and the Lord Spencer, 58. Thus 232 men had set forth from Liverpool to find their fortune in southern seas -- southern, yes, but maybe as close as off the coast near the port of Boston.

I think it would be instructive to go directly to Perkins and to set out selected entries through the years 1799 and 1800. These entries -- at least in respect to Liverpool, Nova Scotia -- will bring the reader back to the docks and the meeting rooms of the time and to give a true flavour to the home-side of the privateering business.

On January 11th, 1799: "... We heave down the Ship Charles Mary Wentworth, and finish the other side. She has a good tallow bottom [fast]. [On February 2nd, the Charles Mary Wentworth goes to sea.]

24 March: ... This evening arrived a Spanish Brigantine, a Prize to the Ship Charles Mary Wentworth & Schooner Fly, taken near Tortuga, from Tenerife, bound to Laguira [La Guaira, Venezuela] with a lading of wine, brandy, dry goods and other articles, ... The Ship & Schooner were left in latitude 22, all well, and in good spirits.

12 April: ... [A Captain] arrives from Boston. Bring news of the Lady Wentworth being blown off the coast and taken by the French. Ellenwood is bound to Halifax. I write Messrs Cochrans, and send them samples of the wine & brandy in pipes, & brandy in demijohns. [I simply observe that a demijohn is a large bottle with bulging body and narrow neck, holding usually about five gallons, and usually cased in wicker- or rush-work, with one or two handles of the same, much used in merchant-ships of those days.]

11 May: [The Privateer Charles Mary Wentworth comes in from sea with prizes, one being a large topsail schooner. The prizes had cocoa in their holds.]

3 June, 1799: [Auction off prizes and their cargoes.] ... The copper bottom Schooner Casualidad is first sold with her guns, carriages, & implements belonging to them. ... The cocoa was next sold ... [the vessels, the Lafortune and Diligence were next sold with cargoes including flour, red wine and blankets.] ... [Owners] meet together at Mr. Taylor's, to consult about fitting out the Prize Brig Nostra Seignora Del Carmen, and agree to get her out with all possible despatch. Captain Freeman is going directly to Halifax to procure guns and other necessities. Thomas Parker is to command her. She is to be rigged a ship.

13 June: ... Captain Freeman arrives from Halifax. Has obtained 10 nine pounders from government, & bought 4 four pounders The ship is named the Duke of Kent (formally, Nostra Seignora Del Carmen), after the new title conferred on His Royal Highness, Prince Edward.

22 June: ... The Duke of Kent goes on very rapidly. We hope will sail by next Wednesday or Thursday. There is upwards of ninety men entered, which is more than the owners wish for. 90 we think sufficient.

28 June: ... The Ship Duke of Kent goes over the bar [to the outer harbour where she was put at anchor]. Makes a very war like appearance.

29 June: [Certain of the owners go aboard the Duke of Kent.] ... The men are mustered on board, a copy of the articles & list of men is taken. They amount to 96 men and boys, all on board, officers included. She is out of sight at 7 o'clock, wind S.W. ...

11 September (Wed): ... He [gentleman from Halifax] confirms the arrival of the Prince [Edward] last Thursday. He was rec'd with great parade & rejoicing. [Prince Edward came from England on the Frigate Arathusia. See Perkins entry of the 14th.]

2 October: [The Duke of Kent returns from her cruise with a captured Spanish vessel (Christo Del Graz) in tow.] She proves to be a Spanish vessel, from La Guaira [Venezuela], bound to Cadiz, computed to have 40 tons cocoa, 2 tons Indigo, & 1 ton of cotton on board ...

16 October: ... The owners of the Privateers meet at my office. Appoint Captain Joseph Freeman to the command of the Duke of Kent; Captain Thomas Parker to the Charles M. Wentworth; Captain John Barrs, Junr., to the Schooner [Lord Spencer] lately purchased.

19 October, 1799: ... All three of the privateers are entering men. The Duke has about 30; the Charles near the same; the Lord Spencer about 20.

20 March, 1800: [Two prizes come in: a Schooner and a Brig. The Schooner (Hazard) carries mostly drygoods Linins, shalls, bombazeens, etc., with 20 boxes of culloshes; the Brig (St. Michael), cocoa and indigo.] ... The Charles M. Wentworth had not captured anything worth sending home, but has considerable money & goods on board. The prizes are alongside each other at Parker's wharf.

11 May: ... Towards evening a sloop is coming into the Harbour. Proves to be a Prize to the Duke of Kent, which she left on the Spanish coast five weeks ago, in company with C. M. Wentworth. The Prize is a Danish vessel, bound from St. Thomas to Carmona, with dry goods and some brandy.

7 June, 1800: At sunrise I hear a gun. It proves to be the Duke of Kent ... [She comes in with a captured brig, the Nostra Senora Del Conception.] She is from Spain, about 100 tons, loaded with wine, brandy & goods.

19 June: ... The Duke of Kent is hove down. Her copper is given out in many places, and has very large barnacles or mussels on her.

4 October: The ship in sight proves to be the Duke of Kent, Thomas Parker. She is come home without taking anything. His Majesty's Ship Neried [the 36 gun Néréide], Captain Watkins, who took away twenty of his best men, which disenabled him so far that he concluded to return immediately. ..."

Come all you jolly sailor lads, that love the cannon's roar,

Your good ship on the bring wave, your lass and glass ashore,

How Nova Scotia's sons can fight you presently shall hear,

And of gallant captain Godfrey in the Rover privateer.

She was a brig of Liverpool, of just a hundred tons;

She had a crew of fifty-five and mounted fourteen guns:

When south against King George's foes she first began to steer,

A smarter craft ne'er floated than the Rover privateer.

Five months our luck held up and down the Spanish Main;

And many a prize we overhauled and sent to port again;

Until the Spaniards laid their plans with us to interfere,

And stop the merry cruizing of the Rover privateer.

The year was eighteen hundred, September tenth the day,

As off Cape Blanco in a calm all motionless we lay,

When the schooner Santa Ritta and three gunboats did appear,

Asweeping down to finish off the Rover privateer.

With muskets and with pistols we enaged them as they came,

Till they closed in port and starboard to play the boarding game;

Then we manned the sweeps, and spun her round without a thought of fear,

And raked the Santa Ritta from the Rover privateer.

At once we spun her back again; the gunboats were too close;

But our gunners they were ready, and they gave the Dons their dose.

They kept their distance after tat and soon away did sheer,

And left the Santa Ritta to the Rover privateer.

We fought her for three glasses and then we went aboard,

Our gallant captain heading us with pistol and with sword;

It did not take us very long her bloody decks to clear,

And down came the Spanish colours to the Rover privateer.

We brought our prizes safe to port -- we never lost a man;

There never was a luckier cruise since cruising first began;

We fought and beat four Spaniards -- now did you ever hear

The like of Captain Godfrey and the Rover privateer?

"with three prizes, an American ship, Whaleman, from the Brazil, with 11 hundred bbs [barrels] Sperma Cetie oil, belonging to New Bedford, a Brig, also American, from Madeira, with wine, bound to Norfolk, both retaken from the French, in Latitude 23, where he fell in with a French Privateer Schooner, with six prizes, of which he got two, an American sloop, bound from New York to Curaco, with goods, which he has brought in from adjudication, expecting her to be a prize. They are all anchored below the point, and with the New York ship, makes a very pretty appearance."Thus on July 4th there was considerable reason to celebrate at Liverpool. That evening and the following one, the "Privateersmen were very noisy in the night, about the wharves, some fighting or wrangling. They are very peaceable today & evening [the 6th]." Within days, on July 16th, 1800, the Rover sailed again, with 60 men and 16 guns. She was gone until the 16th of October when she returned with

"an armed Spanish Schooner, of 10 six pounders, and 2 12 pounder caronades, which after a severe engagement the Rover took, about the 12th of September last, on the Spanish Main. The schooner & two Gun Boats came out on purpose to take the Rover, but by Good Providence, the schooner was captured, & the Gun Boats beat off. From the best accounts they could obtain, there was 53 killed & wounded in the schooner, & many on the gun boats. ... while the Rover had not a man hurt, not even a splinter, as I can learn ... the Rover had only 38 men on deck in this engagement."13It seems that the owners of the Rover spent the next few months repairing her and refreshing her crew. On January 14th, 1801, they "make a beginning to get the privateer Rover ready for sea. We have about 40 men entered." On the 26th, she departed for sea, Joseph Barss, Jr., Commander. Eleven weeks later, on April 18th, the Nostra Sen. Del Carman hauled into Liverpool, a prize that the Rover sent in. "She left her in Moona passage [in the West Indies between Haiti and Porto Rico] upwards of twenty days ago, all well." On May 4th, another prize comes in, "An American schooner. ... She is from Newberry Port, bound to New Orleans, loaded with nails, paint tinware, etc. She was captured near Port Rico." Within a couple days of that, on May 6th, another report on the Rover comes in, to the effect that the Rover was cruising between Bermuda and America. The report is that "Rover's sails are worn very thin and that she will soon be heading for home as Captain Barss has but a few men, 8 of his best having left him. Not long after that, on May 8th, the Rover returned to Liverpool. She was not left to lie long, for on May 11th, the owners were fitting her out again. "Captain Barss declines going. Captain Alex Godfrey has the offer." On June 7th, "the Brig Rover, A. Godfrey, Commander, sails on a cruize, has about 47 men & boys." Some of the prizes, the Admiralty Court refused to condemn, for, as Perkins observed, "the Americans are in favour of Great Britain, and all prize causes will be determined much on their side. No news of the Rover. I think privateering is nearly at an end." On September 5th, "the privateer Rover, returned from an unsuccessful cruize, having taken nothing." But she is not finished, as her papers are still good. On October 25th, we see where "The Brig Rover, a letter of mark, with eight guns, Joseph Freeman, Commander, sails for the West Indies." She had company, as the "schooner Ratler, Enos Collins, Commander, with some guns, also sails for the West Indies." Within days of that news comes in from Halifax "that a packet was arrived from England ... with news of a general peace in Europe. Preliminaries signed the 10th October. There was to be no news of the Rover." On February 20th, 1803, the Rover with her captain, Joseph Freeman, came back to Liverpool from Barbados & St Kitts. She had a "loading of sugar" which implies that while in the fall of the previous year she started out as a privateer, her role shifted to that of a freighter when she received news, possibly from a passing British warship, that the war was over and had been since the signing of the Treaty of Amiens on March 25, 1802.

About a half a century later, in 1853, there appeared an article in the Halifax Monthly Magazine. The following is an extract:

"Captain Godfrey, the hero of the tale, is well remembered by many persons living in Queen's county, and not long ago an old gentleman who was well acquainted with him gave me the benefit of his reminiscences. He described him as a man considerably beyond the ordinary size, of an exceedingly quiet demeanor, and modest and retiring disposition. This will also appear from the 'plain unvarnished' account which he gives of a most gallant action, as well as from the fact that he declined the command of a vessel of war, which was offered him by His Majesty's Government, not long after the action which he describes took place. At the close of the war he disarmed his privateer, and entered into the fish and lumber trade, between Liverpool, N.S., and the West Indies. In the year 1803 he died of yellow fever, and was buried near Kingston, Jamaica.War renewed itself; peace had only lasted only 18 months. A circular letter, dated 16 May, 1803, from Downing Street was received here in Nova Scotia and was communicated to the house on Friday, June the 24th. "'Unfavorable termination of the discussion lately depending between his majesty and the French government,' and that 'his majesty's ambassador left Paris on the 13th.' Letters of marque and commissions to privateers are to be issued, and French ships to be captured, &c. The kings share of all French ships and property will be given to privateers. Homeward bound ships should wait for convoys."15 Three days later, on the 27th, Perkins hears the news from a captain who came in from Halifax. This news prompts Perkins and his friends not to proceed to the West Indies with their loads of fish. The markets were bad, anyway, and if "we add to this we expect insurance will be very high and the risk very great. We therefore give up that voyage & conclude if a suitable crew can be got to send her to Newfoundland with lumber, or otherwise if we hear Alewives & Pollock will answer in the States to send her there."

...

Our readers should be informed that the loyal Province of Nova Scotia (America) having suffered most severely in the early part of the war, from the cruisers of the enemy, fitted out a number of privateers in order to retaliate on, and to extort compensation from the foe. Within these four years, twelve or fifteen ships of war have been fitted out by the Nova Scotians, and of this number one half are owned by the little village of Liverpool, which boasts the honor of having launched the brig Rover, the hero of our present relation.

...

On the 10th of September, being cruising near to Cape Blanco, on the Spanish Main, we chased a Spanish schooner on shore, and destroyed her. Being close in with the land, and becalmed, we discovered a schooner and three gun-boats under Spanish colours making for us; a light breeze springing up, we were enabled to get clear of the land, when it fell calm, which enabled the schooner and gun-boats, by the help of a number of oars, to gain fast upon us, keeping up at the same time a constant fire from their bow guns, which we returned from two guns pointed from our stern; one of the gun-boats did not advance to attack us. As the enemy drew near, we engaged them with muskets and pistols, keeping with oars the stern of the Rover towards them, and having all our guns well loaded with great and small shot, ready against we should come to close quarters. When we hard the commander of the schooner give orders to the two gun-boats to board us, one on our larboard bow and the other on our larboard waist, I suffered them to advance in that position until they came within about fifteen yards, still firing on them with small arms and stern guns; I then manned the oars on the larboard side, and pulled the Rover round so as to bring her starboard broadside to bear athwart the schooner's bow, and poured into her a whole broadside of great and small shot, which raked her deck fore and aft while it was full of men ready for boarding. I instantly shifted over on the other side, and raked both gun-boats in the same manner, which must have killed and wounded a great number of those on board of them, and done great damage to their boats. I then commenced a close action with the schooner, which lasted three glasses, and having disabled her sails and rigging much, and finding her fire grew slack, I took advantage of a slight air of wind to back my head sails, which brought my stern on board of the schooner, by which we were enabled to board her, at which time the gun-boats shoved off, apparently in a very shattered condition. We found her to be the Santa Ritta, mounting ten six-pounders and two twelve-pound carronades, with 125 men. She was fitted out the day before for the express purpose of taking us; every officer on board of her was killed except the officers who commanded a party of twenty-five soldiers; there were fourteen men dead on her deck when we boarded her, and seventeen wounded; the prisoners, including the wounded, amounted to seventy-one. My ship's company, including officers and boys, was only 45 in number, and behaved with that courage and spirit which British seamen always shew when fighting the enemies of their country. It is with infinite pleasure I add that I had not a man hurt; but from the best account I could obtain, the enemy lost 54 men. The prisoners being too numerous to be kept on board, on the 14th ult. I landed them all except eight, taking an obligation from them not to serve against His Majesty until regularly exchanged. I arrived with my ship's company in safety this day at Liverpool, having taken, during my cruise, the before mentioned vessels, together with a sloop under American colours bound to Caracoa, a Spanish schooner bound to Porto Cavallo, which have all arrived in this Province, besides which I destroyed some Spanish launches on the coast."14

The owners did not immediately get the Rover ready for the privateering business. She would have needed to be re-rigged, cleaned and made ready for sea.16 Perkins writes on August 8th, "The Brig Rover is begun to be fitted for a cruize this day." And on the 16th, "The Privateer Rover goes over the bar."17 Perkins made what appears the last entry about the Rover on November 8th, 1803 -- "The Brig Rover privateer is arrived last evening ..." She apparently18 put out to sea again, however, in some manner or other, she and her captain were to get into some difficulty. Benning Wentworth, the provincial secretary, wrote Joseph Freeman of Liverpool, "Because of the improper conduct of the commander of the brig Rover towards an American vessel, the Lt. Governor has suspended the licence under which, in lieu of a letter of marque, the brig was operating."19

The War of 1812

In a subsequent chapter we will consider in some detail the events leading up the War of 1812, a war which pitted the young United States of American against Great Britain. Sufficient to write here that the Americans were fed up with British naval ships arresting American ships and the impressment of seamen. Though there were attempts by the parties to ameliorate their differences as early as 1795 (The Jay Treaty), the situation become progressively worse, such that, on June 18th, 1812, the American Congress at President Madison's urging declared war on Britain. It marks the beginning of the last of the privateering periods in Nova Scotia.

Privateers put to sea from a number of ports in Nova Scotia. They were very active in the first year of the war. By the close of 1813, Nova Scotia privateers had brought in 106 prizes. Between 1812 and the end of the hostilities in 1815, they brought in "200 prizes, exclusive of a number of recaptures."20

There were a number of successful privateers operating in this last period. One was the Liverpool Packet. The Liverpool Packet was as famous as any other, including the Rover.

The Liverpool Packet was originally a tender to a Spanish slaver, captured and auctioned at Halifax in November 1811. It was intended by the purchasers to use her as a packet to run between Liverpool, Nova Scotia and London, England. Thus an explanation of her name. The War of 1812 changed these plans. She was fitted out as a privateer. Snider wrote of the the Liverpool Packet when she sailed from Liverpool for her first cruise.

| "On the last day of August [1812] the Liverpool Packet hoisted the Red Jack and put to sea as a privateer, victualled for sixty days, with 200 rounds of canister and 300 of roundshot in her magazine, four hundred-weight of gunpowder, two anchors, two cables, 300 lbs. of spare cordage, and twenty-five muskets and forty cutlasses for her forty-five men. She had five guns, one 6-pounder, two 4-pounders, and two 12-pounders. John Moody, Halifax importer of foodstuffs and general merchandise, and Col. Joseph Freeman, of Liverpool, N.S., had joined with Enos Collins in providing the £1,500 bail for her good behaviour."21 |

|

The owners of the Liverpool Packet were Enos Collins, Benj. Knaut, John and James Barss, all of Liverpool. Subsequently she was owned by "Collins & Allison, of Halifax; Jos. Freeman and C. Seely, of Liverpool." The first prize was a Portuguese ship, the 291 ton Factor, captured on 7th September, 1812. The Factor with a prize crew aboard was sent to Liverpool. Within weeks, during November the Liverpool Packet put to sea again, this time under the command of Joseph Barss. On her first two cruises and before the year was out, she sent in, in addition to the Factor, eighteen prizes ranging from a small 39 ton sloop, Susan, to the 134 ton schooner, Four Brothers. (It is to be remembered that the size of the Liverpool Packet was 67 tons.)

"No privateer of the provinces ever came home with greater evidence of her industry than did the Liverpool Packet when, all iced up, and with her last two prizes, the Columbia and the Susan, following, she rolled into Liverpool on December 21st, 1812, just in time for Christmas. Twenty-one prizes were moored to her credit in the Liverpool river."25

The Liverpool Packet was bought for £420 and during her short career it is thought that she made upwards of a million dollars for her owners.26 We learn from a Naval Heritage Web Site27 that she was most successful off the New England coast, especially in the spring of 1813. In one week she captured 11 vessels off Cape Cod. In another five day period, she captured four schooners. She also made several landings in the Elizabeth Islands and at Wood's Hole. At these places, we presume, she relieved the citizens of their money and goods. Shortly thereafter, on June 9th, her career as a Nova Scotia privateer came to an end.

"[A]fter a stubborn fight she was forced to surrender to an American privateer, the Thomas [Captain Shaw], a vessel of twice her size.28 Great interest was taken in her capture, for her career had been so bold and daring that Captain Barss was regarded as capable of meeting any emergency. ... Greatly outnumbered, they were compelled to surrender, but not before several of the crew of the Thomas had been killed. Captain Barss was taken to Portsmouth and there closely confined by order of the American Government. Through the influence of Governor Sherbrooke, his release was secured in the course of a few months."29

After her capture, the Liverpool Packet was sold at auction and renamed Young Teazer`s Ghost and used as an American privateer. Later she was renamed the Portsmouth Packet. Within four months, October, 1813, the Portsmouth Packet was captured by H. M. S. Fantome off Mount Desert Island, Maine, after a chase of thirteen hours. She was brought into Halifax and restored to her former owners. She was soon cruising again as the Liverpool Packet under the command of Caleb Seely. Before the year was out, she sent in fourteen prize vessels. She continued her successful career as a privateer through the year of 1814. She contributed to the prize list for May and June. In August, she took two prizes while acting in concert with the Shannon,30 the pair were working off of Bridgeport and New York. The Liverpool Packet continued to work often with British naval vessels right to the war's end.

The privateer of one country, through its capture, could soon be turned out as the privateer of another. As it turned out, the Thomas, who captured the Liverpool Packet in June of 1813, was in turn captured and soon sailing out of Liverpool as the Wolverine under a letter of marque dated 21st August, 1813. Barss who was the captain of the Liverpool Packet when captured by the Thomas was to become one of her new owners. She apparently was better fitted out as the Wolverine then when she was known as the Thomas. As already mentioned in describing the Thomas (renamed the Wolverine), she carried 10 to 12 guns and a compliment of 80 men. In addition, the men on the Wolverine had readily available to them 37 muskets, 40 boarding pikes, 10 pairs of pistols and four swivels. The records disclose that the Wolverine had two letters of marque. One was dated August 21st, 1813, and thereon were listed the owners: Messrs. W. Shea, Barss, J. Freeman and Benj. Knaut -- all of Liverpool. The second letter of marque was dated November 18th, 1813 (John Roberts, Captain).

The success of the Liverpool Packet prompted the people of Liverpool to get more privateers fitted out. Two of them were the Sir John Sherbrooke31 and the Retaliation. The Sir John Sherbrooke was formerly the American brig-of-war Thorn which had been captured on October 31st, 1812, by the British frigate, the 38-gun Tenedos, and as was sold at Halifax as a prize. Snider described the Sir John Sherbrooke as the "largest and finest of all privateers of Nova Scotia."32 She was of 273 tons.33 "Eighteen long nine-pounders grinned from her gunports, nine on each side; and she had bridle ports cut in the bows, where two chase guns could be shifted, for firing straight ahead. Eighty cutlasses and boarding pikes hung in racks around her masts. Fifty muskets filled her arms chest."34 The Sir John Sherbrooke had three letters of marque issued to her: 27th November, 1812 (Captain Thomas Robson), 15 February, 1813 (Captain Joseph Freeman), and 27th August, 1814 (Captain Wm Corken). The Sir John Sherbrooke achieved greater success in a shorter period of time than any other armed vessel. In her cruise which started in February of 1813, "she captured no fewer than sixteen prizes."35 The months of March, April, May and June of 1813 were very good ones for the Sherbrooke. This is demonstrated by the following excerpts of the diary of John Liddell, a merchant at Halifax.

Late in 1813, the Sir John Sherbrooke gave up prize-hunting and entered the carrying trade.37 She came to her end in the autumn of 1814 on American shores. While outward bound from Halifax with a cargo of oil and dried fish, the American privateer Syren captured her. A prize crew was put aboard with the view to getting her into an American port. While so proceeding, a British squadron came along. The Sherbrooke was chased ashore before she could make port. The American crew managed to get away with all the valuables on board, and did so under the fire of the British frigate's guns. Boats from the frigate attempted a rescue, but were driven off by the guns of a nearby fort. Salvage of the Sherbrooke being impracticable, she was set on fire and burned to the water's edge.38

As for the Retaliation, she was a 61-foot long schooner of 71 tons, 5 guns and a normal compliment of 50 men.39 Her shares were owned by men from Liverpool. The Retaliation had three letters of marque issued to her. The first was dated February 10th, 1813 (Captain Thomas Freedom). The second, dated May 27th, 1813 (Captain Benj. Ellenwood). And the third, dated December 22nd, 1814 (Captain Harris Harrington). Her first capture was in March of 1813. During her several cruises that year she took fourteen prizes. The Retaliation, while on her last cruise in October 1814 was captured at a place among the Elizabeth Islands, off the south-west corner of Cape Cod. "The armed schooner Two Friends discovered the Retaliation at anchor in a small cove, and, it being calm, sent off her boats to engage. When within three-quarters of a mile of the Retaliation, she fired her long gun twice at them, and they came to anchor. The Retaliation then sent her boat with the captain and five men to board the Two Friends. The Americans kept under cover until the boat got alongside and was made fast, when upon a signal from their captain about twenty of them rose up and presented their muskets into the boat, with the threat that upon the least resistance they should be instantly killed."40 Faced with this predicament, the captain gave the Retaliation up. It would not appear that she ever returned to sea as a Nova Scotian privateer.

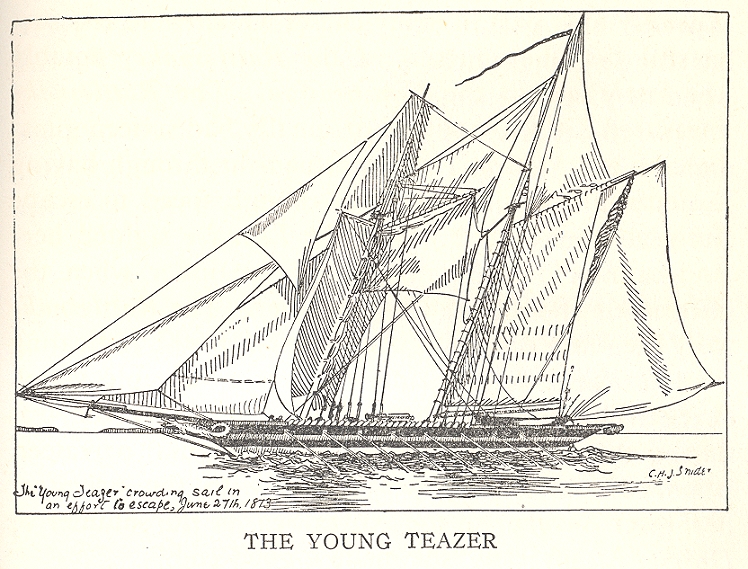

We have in this work concerned ourselves with the privateering activities of Nova Scotians. These activities hurt the Americans to a very great extent. One should not conclude, however, that there were no American privateers operating in the waters off of Nova Scotia. I am not aware of any study having been carried out, but from my general reading, it seems, there was as many if not more American privateers preying on Nova Scotians than Nova Scotian privateers preying on Americans.41 It was so during the years of the American Revolution,42 and so through the years of The War of 1812. The most famous American privateer operating in Nova Scotian waters at this time was the Young Teazer. Her fame is due to her spectacular demise.

"At length the stern settled on the bottom, in water twenty five feet deep, but the alligator jaws still gaped defiantly above the tide."47 The Teazer, though in pieces throughout, can yet be found in the picturesque village of Chester.

"The Young Teazer was a specially-built privateer, hailing from New York; schooner-rigged, sharp, and seaworthy; black-hulled, coppered43 to the bends to keep her clean of sea-growths and barnacles and make her slip through the water. She had a carved alligator, with gaping jaws, for a figurehead. She was large, for her class -- 124 tons measurement, and about seventy-five feet in length; but she was so fine lined that her crew could drive her at a rate of five knots in smooth water, when there was no wind, with her sixteen long sweeps. It was this uncanny ability to move about while other vessels stood stock still or drifted astern in the calms which accounted for her success."44

On June 27th, 1813, the Sir John Sherbrooke, a privateer which we dealt with earlier, was pursuing the Young Teazer not far from the mouth of Halifax Harbour. During the chase, the Teazer had the misfortune to fall in with a British naval ship and was chased into Mahone Bay. The British warship was the 74-gun La Hogue. The wind dropped and the Teazer was obliged to get out her sweeps. La Hogue got her small boats over her sides and they pulled her, in shifts, ever closer to the Teazer. There then occurred a violent explosion which blew the Young Teazer out of the water. Of her thirty-six crew, only seven lived.45 It seems that one of the crew thought that instant death was better than being captured by the British. He threw a burning coal into the powder magazine.46

"The remains of the Teazer was [were] towed into Chester Bay the next day and beached on what is now Meisner's Island. The hull was sold and was used for the foundation of what is now the Rope Loft Restaurant. Part of her keelson was used to make the wooden cross that can be found in St. Stephen's Church, Chester."48

[NEXT: Bk. 2, Pt. 5, Ch. 4 - "The Seafaring Life."]